Weight matters in heart valve disease

Why is weight important in valve disease?

Being overweight increases the body’s need for oxygen and worsens the effect of any type of valve disease. Reducing weight can delay and occasionally even avoid the need for surgery. Being severely overweight makes operations more risky and the recovery from them slower. Furthermore, replacement heart valves can be less effective if you are overweight.

If you are overweight, reducing weight reduces the risk of many other conditions such as heart attacks, high blood pressure, some types of cancer and type 2 diabetes.

What is a healthy weight?

A BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 is considered a healthy weight. 25-30 is considered overweight and >30 is considered obese.

Many local authorities are able to help you with weight loss by dedicated programmes; please contact your GP to see if there is a scheme in your area.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a measure of your height and weight to help work out if your weight is healthy. You can calculate your BMI on the NHS website https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/healthy-weight/bmi-calculator/

How do I achieve a healthy weight?

- Changes to your diet

People become overweight because they eat more energy (calories) than they burn. This can be due to eating large portions, frequent snacks or sugary drinks, or due to doing too little physical activity.

Healthy eating is about eating a variety of foods in the right amount. There are groups of food that we should eat more of, like starchy foods that are high in fibre (like brown rice and brown bread) and fruit and vegetables, and there are some foods that are high in sugar or highly processed that we should eat less of.

- Exercise

Any activity is good, even walking, This will not harm your heart valve disease. Try these simple changes:

- Use stairs instead of lifts

- Get off the bus a stop early and walk the last bit

- Walk every day. If you have a smartphone or watch, aim for 10,000 steps a day.

- Track your weight

Weight yourself weekly to ensure that your hard work is reaping results. Some people find organised weight loss clubs to be helpful with support and motivation in their weight loss journey.

Exercise in heart valve disease

Unless instructed not to by your healthcare professional, it is very important that you maintain physical activity as part of a healthy lifestyle. Exercise not only helps you keep physically fit but is also fantastic for your psychological health.

Gentle exercise to the extent that makes you mildly short of breath should be encouraged in virtually all heart valve disease patients. If you want to take part in more intensive exercise, it is likely that this will be safe however it is important that you discuss this with your healthcare professional as advice regarding different sports is often very specific to your underlying valve condition.

It is possible that your healthcare professional may wish to do an exercise test such as a treadmill test or bike stress echocardiogram to further assess your ability to undergo more strenuous exercise.

Some patients with aortic valve disease also have a stretch on the aorta known as an aneurysm. If you have an aneurysm it is likely that your doctor will advise you to avoid heavy weights such as weight lifting.

If you have a mechanical valve replacement and you take warfarin then it is likely that your healthcare professional will advise you to avoid contact sports and any sports where you are at an increased risk of a head injury.

Smoking

It is very clear that smoking is bad for your health. The chemicals in cigarettes lead to cholesterol plaque build-up in your heart arteries. There is also evidence that smoking increases the rate of progression of aortic stenosis. Smoking also affects the lungs leading to COPD and increases the risk of various cancers.

It is very important that you give up smoking if you have heart valve disease. Your GP can signpost you to stop smoking services. If you get support at the time you decide to give up, you are more likely to quit.

If you are still smoking at the time you require valve surgery, the surgeon may refuse to operate until you have agreed to give up. This is because smokers are at increased risk of complications such as pneumonia in the recovery phase following heart valve surgery.

Alcohol

Although some alcohol in moderation is not considered harmful, alcohol in excess of the recommended limits can lead to negative effects on your heart including high blood pressure and a directly toxic effect causing heart failure.

Government recommendations suggest that it is safest to drink less than 14 units per of alcohol per week, spread evenly over 3 days or more. Binge drinking should be avoided.

Alcohol can also interact with warfarin medication and cause levels of blood thinning to be erratic. You should speak to your healthcare professional about the interaction between alcohol and warfarin.

Finally alcohol contains a significant amount of sugar and calories. If you are already struggling with being overweight then the additional calories that you consume when you consume alcohol can exacerbate this problem. You may find that stopping drinking alcohol leads to a weight loss without having to change your diet significantly.

Piercings and tattoos

Patients with heart valve disease have an increased risk of a condition known as endocarditis. This is a serious but rare condition where bacteria enter the bloodstream and latch onto the heart valves causing damage to the heart valves and a bloodstream infection. Any procedure which breaks the skin potentially exposes you to an increased risk of bacteria entering the bloodstream. For this reason, it is advised that patients with heart valve disease do not have tattoos or piercings as these can lead to an increased risk of endocarditis.

Pregnancy and childbirth

Pregnancy has implications for native (unoperated) valve disease, aortic enlargement and replacement heart valves.

It is important that you discuss family planning with your GP or in the specialist valve clinic well ahead of becoming pregnant. Contraception should be discussed and progestogen-only pills or devices may be advised. It may be appropriate to plan a family before the valve disease is severe enough to require surgery, to avoid the problem of how to manage a replacement valve.

Your pregnancy and delivery should be discussed with a cardiologist, obstetrician and anaesthetist who will jointly agree a plan suitable for you as an individual.

The increase in blood volume during pregnancy can bring on symptoms.

The aorta enlarges by 1-2 mm during pregnancy in a normal woman so the risk of severe enlargement and tearing are higher if the aorta is already large before the pregnancy.

The World Health Organisation recommends extreme caution against becoming pregnant if you have the following conditions:

- Severe mitral stenosis even if asymptomatic

- Aorta larger than 45 mm with Marfan syndrome or larger than 50 mm associated with a bicuspid aortic valve

- Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (can cause aortic tears)

- Severe aortic stenosis with symptoms

- Any cause of a severely reduced LV function (including severe aortic and mitral regurgitation)

Native (unoperated) valve disease

Aortic or mitral regurgitation even when severe should not cause a problem provided that the LV is well-compensated. If surgery for mitral prolapse is necessary then this should be possible with a repair which would not compromise future pregnancies.

Severe mitral stenosis is a reason for avoiding pregnancy even if it is causing no symptoms. It should be treated, ideally using balloon valvotomy.

Aortic stenosis requires the most thought. One option is to aim to complete a family before the valve disease becomes severe. If the aortic stenosis is already severe then exercise-testing helps to ensure that there are truly no symptoms. Normal exercise capacity suggests a low risk from an imminent pregnancy.

However your cardiologist also needs to judge the likely rate of progression since it may obviously take a while to become pregnant and even the 9 months of pregnancy can be long enough for symptoms to develop. A decision may have to made about having surgery a little earlier than otherwise.

If surgery is needed before pregnancy there is no simple solution. In general, what is good for the mother is bad for the fetus and vice versa. A young woman usually requires a mechanical valve since this lasts a life-time, but with a mechanical valve comes the need for warfarin which can increase the risk of fetal malformation. For this reason, the prescription is usually changed to heparin in the first trimester. Even so, the mother is still exposed to the real risk of valve thrombosis.

Choices in this situation include:

- Implant a biological valve until the family is completed and then implant a mechanical valve when the biological valve fails (which can be in under 5 years in younger people)

- Consider a Ross procedure which is expected to last much longer than a conventional biological replacement valve

- Implant a mechanical valve with management of anticoagulation by a team around pregnancy (see below).

If you become pregnant without preparation or the valve disease advances and causes problems during pregnancy then it is important to be cared for by a team including an obstetrician, cardiologist, anaesthetist and cardiac surgeon. There are no easy rules and the plan will depend on many factors related to the valve disease and the pregnancy. Possibilities could include:

- Medication and careful follow-up sometimes with a hospital admission towards term

- Caesarian section close to term immediately followed by cardiac surgery

- Balloon treatment or cardiac surgery ideally in the middle trimester when the risk to the fetus is at its lowest (although still high)

Replacement valve

The first step is to check that the replacement valve and the rest of the heart are functioning normally. This applies to biological as well as mechanical valves.

The next step if you have a mechanical valve is to discuss the management of anticoagulation. This is hard because there are no easy answers. Unfortunately, there is a risk of dying or losing your baby however good your care is.

The main problem with warfarin is that it doubles the rate of fetal malformations when taken at a dose higher than 5 mg daily (from about 2 in 100 to 4 in 100). There is also a risk of bleeding at delivery in mother or fetus. The INR level (the blood test measure of how thin or sticky your blood is) in the fetus can remain high even when it has fallen to normal in the mother.

Subcutaneous heparin is much safer for the fetus but is less effective in preventing blood clots in the mother.

In general the options are:

- Stay on warfarin throughout the pregnancy, especially if the dose is 5mg or lower and change to subcutaneous heparin just preterm

- Change to subcutaneous heparin for the first trimester (when organs are being formed) then revert to warfarin until just preterm. The heparin must be monitored by measuring a special blood test known as ‘anti-Xa levels’

- Subcutaneous or intravenous heparin throughout. This carries a high risk of clots and maternal death

Most people choose the second option, to have heparin in the first trimester then change to warfarin, but this must be an individual choice made after careful discussion with your obstetrician and cardiologist.

Anticoagulation during pregnancy requires careful monitoring with frequent visits for blood tests.

Is there a risk my condition can be passed on to family members?

Most heart valve disease is due to acquired disease such as wear and tear (degenerative), infection or rheumatic fever.

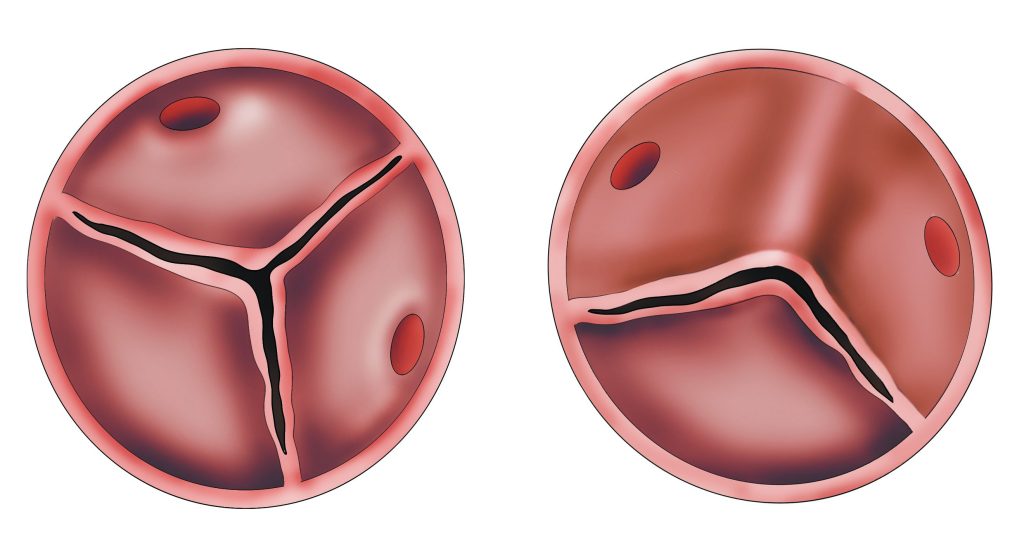

The exception to this rule is bicuspid aortic valve disease and sometimes in mitral valve prolapse. Bicuspid aortic valve disease does appear to have a genetic component. There certainly are families where bicuspid aortic valves are more common, but there does not appear to be a single gene that causes this, and therefore genetic testing is not helpful. If you have a bicuspid aortic valve, your healthcare professional may suggest a one-off echocardiogram in your first-degree blood relatives. If this echocardiogram shows that the leaflet is normal (i.e. not bicuspid) then there is no need for further follow-up in this family member.

Certain conditions causing a stretch on the aorta (aortic aneurysm) are related to underlying genetic abnormalities and your healthcare professional will consider a referral on to the genetics team for dedicated genetic testing and screening of your family members if it is deemed appropriate.

Frailty in heart valve disease

Frailty is a term used to describe the ageing process. With age, bodies gradually lose their in-built reserves leaving us vulnerable. A decline in health in older people can be triggered by an infection or fall. People with frailty often have reduced muscle mass, weight loss and other medical conditions such as poor eyesight or hearing and/or memory problems.

Frail people may struggle with day-to-day activities and require help with things such as housework and self-care. This struggle with everyday living often makes patients very tired and exhausted.

There are things you can do to reduce your risk of frailty including maintaining good activity levels such as walking and strength training, eating well with a high protein diet and keeping your mind active.

As heart valve disease is more common in older people, frailty and heart valve disease often coexist. It is not clear, sometimes, whether people will benefit from treatment of the heart valve disease when they are experiencing significant frailty.

Part of your assessment for intervention for heart valve disease may include tests such as memory tests, sit to stand tests and walking tests.

Heart valve disease during non-cardiac surgery

Heart valve disease is a chronic condition and as such many patients live their day-to-day life with a heart valve problem. If you have another medical condition that requires an operation then you should tell your treating team about your heart valve condition.

In the vast majority of patients with heart valve disease, an operation for a health problem not related to your heart can often go ahead without any further precautions. Your treating team may wish to get an up-to-date echocardiogram prior to your operation. They will usually contact your treating cardiologist to check that the proposed operation is safe.

In a small number of cases, usually in severe aortic or mitral stenosis, there may be a recommendation from your cardiologist that you undergo heart valve intervention in order to go ahead with necessary non-cardiac surgery. These often difficult decisions and taken by the heart valve team in multidisciplinary meetings.

Deciding between a mechanical (metal) and bioprosthetic (tissue) valve

If you need a replacement valve most patients prefer to share the choice of valve type with their physician or surgeon. Some prefer to leave it all to the doctor. It is your choice.

There is good evidence that being part of the choice improves quality of life after surgery.

It is really important that you are as involved as you want to be.

Your cardiologist or surgeon should allow you to ask all the questions you want.

If you have researched your condition, bring this information to your consultation so that you can have a discussion about your care.

Life on warfarin

Warfarin is a blood thinner that reduces the risk of blood clots forming on your heart valve and then being released around the body. In the most catastrophic circumstance a blood clot could reach the brain and cause a stroke.

For obvious reasons it is important that you have good compliance with your warfarin therapy to protect you from blood clots.

Warfarin is a medication that you take on a daily basis. When you are taking warfarin you will need regular blood tests known as INR tests. These blood tests can be performed at your local warfarin clinic, sometimes via your GP or via a home testing kit. Your INR levels often become stable over time but can be influenced by a number of things including your diet, levels of alcohol intake and interactions with other drugs. This means that your dose of warfarin often needs changing in order to keep your INR level within the normal range.

Once patients get the hang of taking warfarin and monitoring the INR they often find it a smooth process.

Although INR self-monitoring machines (in the UK these are called Coaguchek XS and INRatio) cannot currently be obtained on prescription, they can be bought for around £500-700. The strips used for the kits should be available on prescription from your GP, although we are aware that sometimes there is a ‘postcode lottery’ regarding this provision.

If you take warfarin you will be advised to avoid contact sports or activities where there is a risk of a head injury.