Surveillance following valve surgery

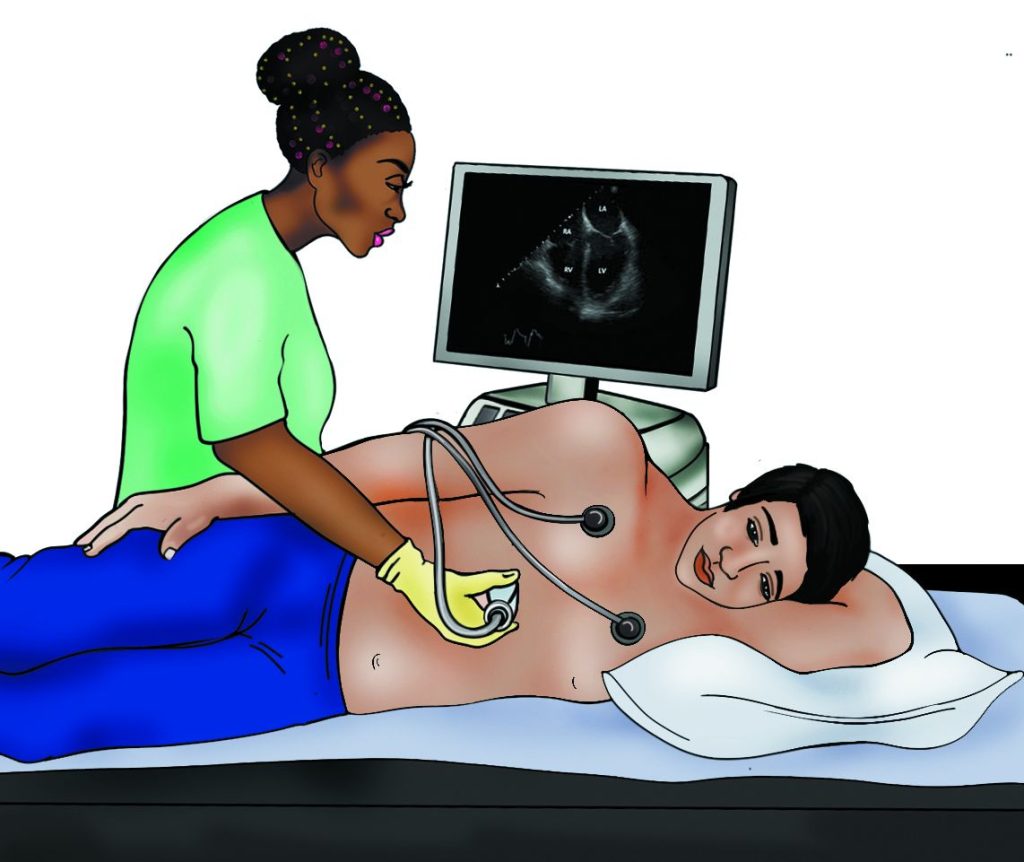

Once you have had an intervention on your heart valve you will be discharged from hospital. You should have a post-operative echocardiogram around 6 to 8 weeks following your valve intervention, to understand how your new valve is working.

Heart valve disease is a condition that you will carry with you for your whole life. You are therefore likely to remain under the care of a valve surveillance programme, undergoing regular clinical review and sometimes echocardiograms, depending on the type of valve operation you had.

You may develop problems with your heart valves further down the line. Once again, it is important that you declare any symptoms to your healthcare professional, so they are able to fully evaluate you and assess the situation.

It is also important that you are aware of the risks of endocarditis and follow the advice regarding prevention. You also need to be aware of the warning signs and symptoms.

Deciding on timing of intervention

It can be very difficult to decide on the right time for intervention This will be different for every single valve condition and to a certain extent for different patients, depending on their circumstances.

Most patients will be taken through a multidisciplinary team meeting prior to a decision being made. This is to ensure as far as possible that timing is right, the type of intervention is appropriate, and the patient is part of the decision-making process.

Your healthcare professional will discuss all these factors with you at your valve clinic appointment. It is very important that you declare any symptoms to help guide this decision. Bear in mind that even when you do not have any obvious symptoms, if the echocardiogram or other imaging tests suggest that the valve needs attending to, the decision to intervene may be the right one.

Watchful waiting

Most people with valve disease have no symptoms, and while doctors may wish for a “crystal ball” to tell when surgery may be necessary, there is no sure-fire way to predict this, although medical science is working on it.

Everyone is an individual and valve disease progresses at different speeds in different people. Although there are general rules to guide cardiologists, each person usually needs to be followed in a clinic until a change announces that the right time for surgery has arrived. This period is called ‘watchful waiting’.

The main reasons for surgery are symptoms, or reaching a threshold on the echocardiogram. Watchful waiting involves seeing a health professional and having an echocardiogram.

Mild valve thickening or regurgitation usually progresses slowly and may not need repeat clinic visits, although your cardiologist may recommend echocardiograms every 3-5 years.

For people with moderate or severe valve disease follow-up is typically every 6 months to 2 years depending on the severity, but might be more frequent if close to agreed thresholds for surgery.

People with an enlarged aorta may have a CT scan or magnetic resonance scan for monitoring as well as an echocardiogram. Sometimes the cardiologist may check the CT or magnetic resonance scan (MRI) every few years, or may only repeat a scan as a check if the measurement on the echocardiogram is close to a threshold for surgery.

The most important aspect of a clinic visit is to check for symptoms. This is where you, the patient, need to step up to the mark, because only you actually feel the symptom.

For most people with valve disease who feel generally well, it is easy to understand why they would want to put off surgery, even though they’ve been told surgery has to happen at some point. It is wrong to be too introverted and oversensitive but at the same time you have to be aware of your body and not ignore signs of change. Try to be mindful of any change, such as being out-of-breath on an activity you could previously do easily.

The first sign of trouble in aortic stenosis can be very subtle. It can be a slowing down, or taking a lift more often, or avoiding hills. Slowing down is an unconscious way to avoid getting chest pain or breathlessness.

Because slowing down can disguise the development of symptoms and may be hard to detect, exercise testing is recommended in most patients with severe valve disease who are symptom-free. Between a third and a half of people with severe aortic stenosis have symptoms revealed by an exercise test.

Sometimes cardiologists use a blood test to check progress. A heart under strain secretes many hormones and other chemicals. The most frequently tested is the BNP level.