What is heart valve disease?

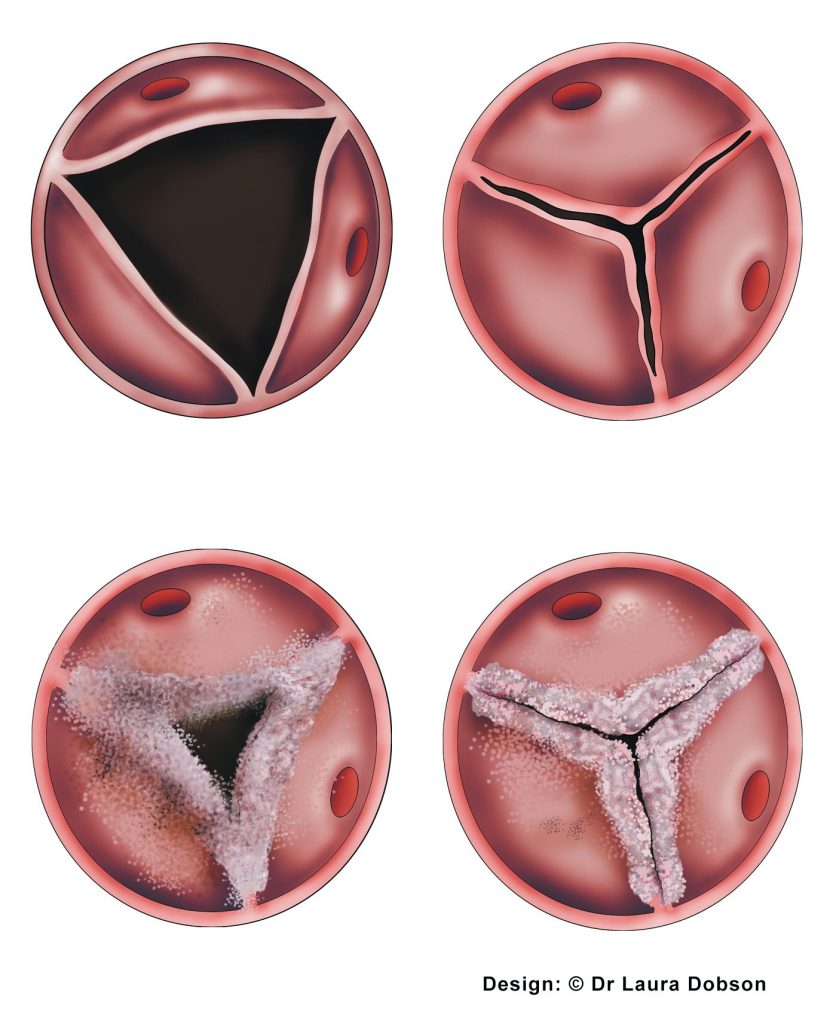

Heart valve disease is a condition where the heart valves do not work as they should. They can either become leaky (regurgitant or incompetent) or narrowed (stenotic).

Mild heart valve degeneration is considered a normal part of the ageing process, and it is common to have mild regurgitation of the heart valves as you get older.

You can be born with heart valve disease or can develop it later. Heart valve disease affects people from all walks of life and is very common – it is likely if you ask around that you will know someone with heart valve disease!

What are heart valves?

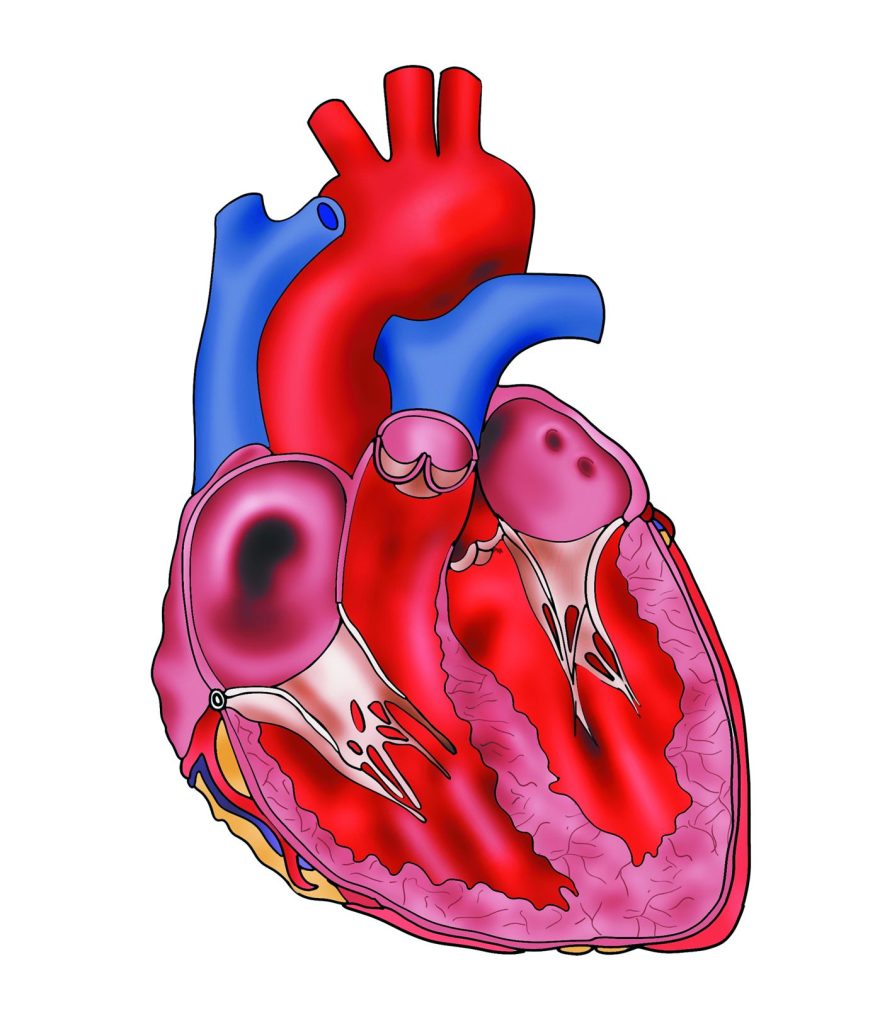

There are four valves in the heart. They allow blood to be directed around the heart and when working normally ensure the blood flows in one direction. They open and close with every heartbeat – that’s 100,000 times a day!

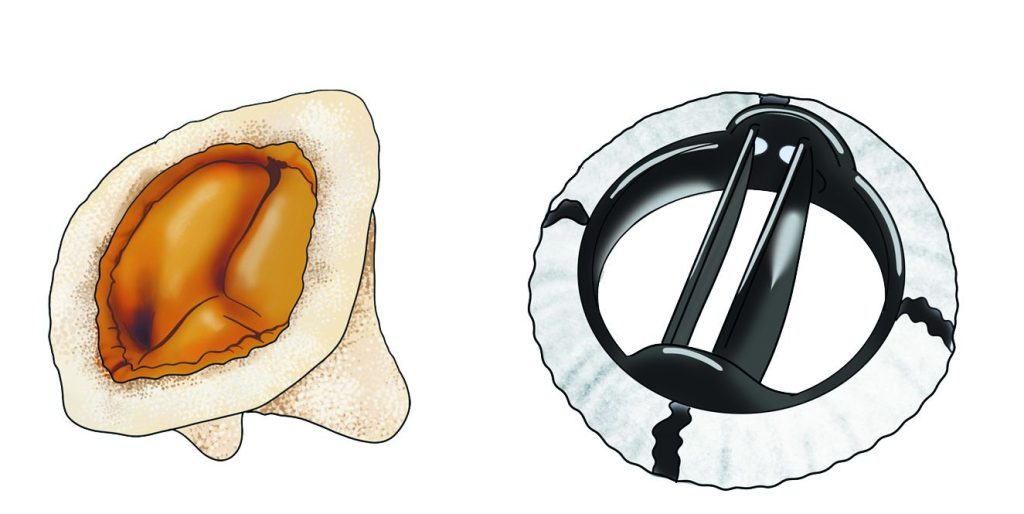

The heart valves open to allow blood to flow in the correct direction then close to stop reflux (or regurgitation) backwards. Each flow has an inlet and an outlet valve. The inlet valves are the mitral on the left and the tricuspid on the right. The outlet valves are the aortic on the left and the pulmonary on the right.

‘Blue’ (unoxygenated) blood from the body enters into the right side of the heart and is directed by the two right-sided heart valves (the inlet tricuspid valve and then the outlet pulmonary valve) towards the lungs where it is oxygenated and turns into ‘red’ blood.

Red oxygenated blood is sent from the lungs to the left side of the heart. It then passes across two valves (the inlet mitral valve then the outlet aortic valve). When it leaves the heart, it provides the body with oxygen.

What causes heart valve disease?

Heart valve disease can be caused by a number of different problems, including

- Wear and tear (degeneration)

- Rheumatic fever (rare in developed countries)

- Endocarditis (an infection of the heart valve)

- Congenital (in people born with an abnormal heart valve)

- Connective tissue disorder (abnormalities of the collagen content such as Marfans syndrome or Ehler’s- Danlos Syndrome)

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Heart failure

- Stretched atria (top chambers of the heart) – usually due to longstanding atrial fibrillation

- Following a heart attack (rarely)

How do I know if I have heart valve disease?

Symptoms are what the patient feels and signs are abnormalities detected by a doctor. Valve disease often causes no obvious symptoms even when it is quite far advanced.

Often, the first tell-tale sign is “silent” to the patient, but not to a doctor with a stethoscope. It’s a murmur that might be detected during a routine health check

at your GP surgery, or at a special clinic for an illness not related to the heart.

But sometimes heart valve disease does make itself known with symptoms. These can also occur with other types of heart disease or lung disease so they are not specific to valve disease. However, if you already know you have valve disease then you must assume that valve disease is the cause. These are the most common symptoms you need to look out for:

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain or heaviness

- Dizziness or blackouts on exertion

- Fatigue / slowing down

- Palpitations

- Ankle swelling

How is heart valve disease detected?

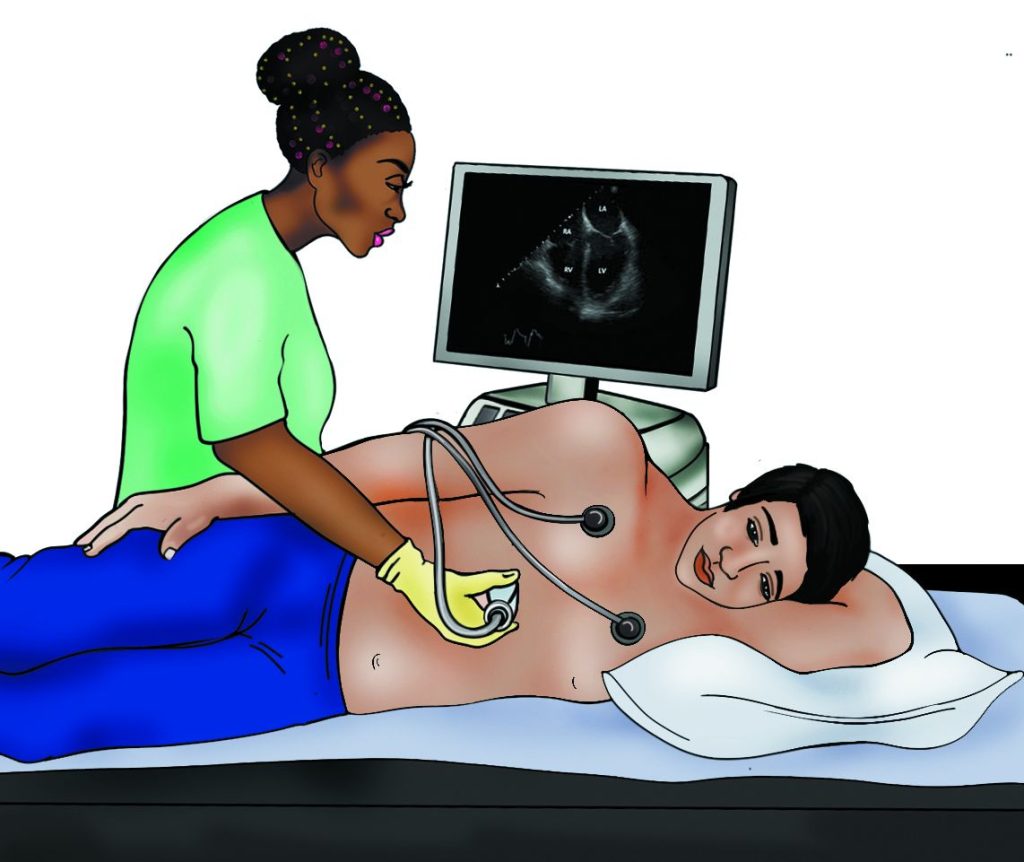

Valve disease can often be detected by listening with a stethoscope, but the ‘gold-standard’ way is with an echocardiogram, an ultrasound scan of the heart.

Your cardiologist may decide that additional tests are needed to check on the severity of the valve disease or to decide the risk of problems developing, even if you have no symptoms. Finally, some tests are done as a prelude to surgery.

Tests for patients with heart valve disease

- Cardiac monitor

- Stress echocardiogram

- During the procedure

- Preparation before a transoesophageal echocardiogram

- Transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE)

- 6 minute walk test

- Exercise stress test (treadmill or bike stress test)

- Echocardiogram (echo or cardiac ultrasound)

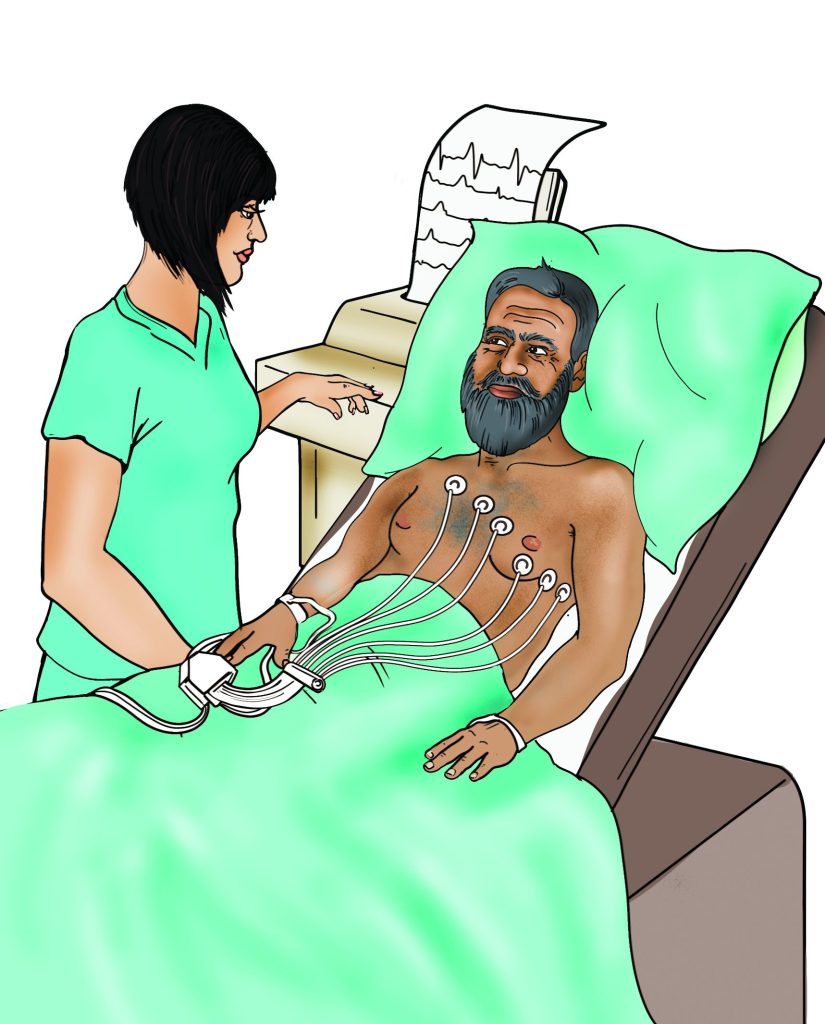

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

- Chest X-Ray

- Blood tests

- Basic observations (blood pressure, pulse, oxygen levels)

- Stethoscope check

- Cardiac catheterisation (Coronary angiogram)

- Cardiac magnetic resonance scan (CMR / MRI scan)

- Computerised tomography (CT scan)

Who does heart valve disease affect?

Heart valve disease can affect people at any stage of their life. Some people are born with heart valve disease (congenital) and others develop the condition as the get older (degenerative) or due to other medical conditions (see causes of valve disease).

It affects both men and women and people from all different walks of life.

Treatments for heart valve disease

- Heart valve intervention

- Medications

- Keyhole techniques

- Heart valve surgery

- Palliative care in heart valve disease

- Valve replacement

Lifestyle

As with any type of heart disease, it is important that you follow a healthy diet, keep your weight within a normal range and do not smoke. Most patients with aortic regurgitation will be encouraged to take regular gentle exercise but you should check this with your doctor. If you have a stretched aorta (the main blood vessel exiting the heart) you are advised to avoid heavy lifting.

If you are planning pregnancy, you should discuss this with your doctor first and let them know immediately if you become pregnant.

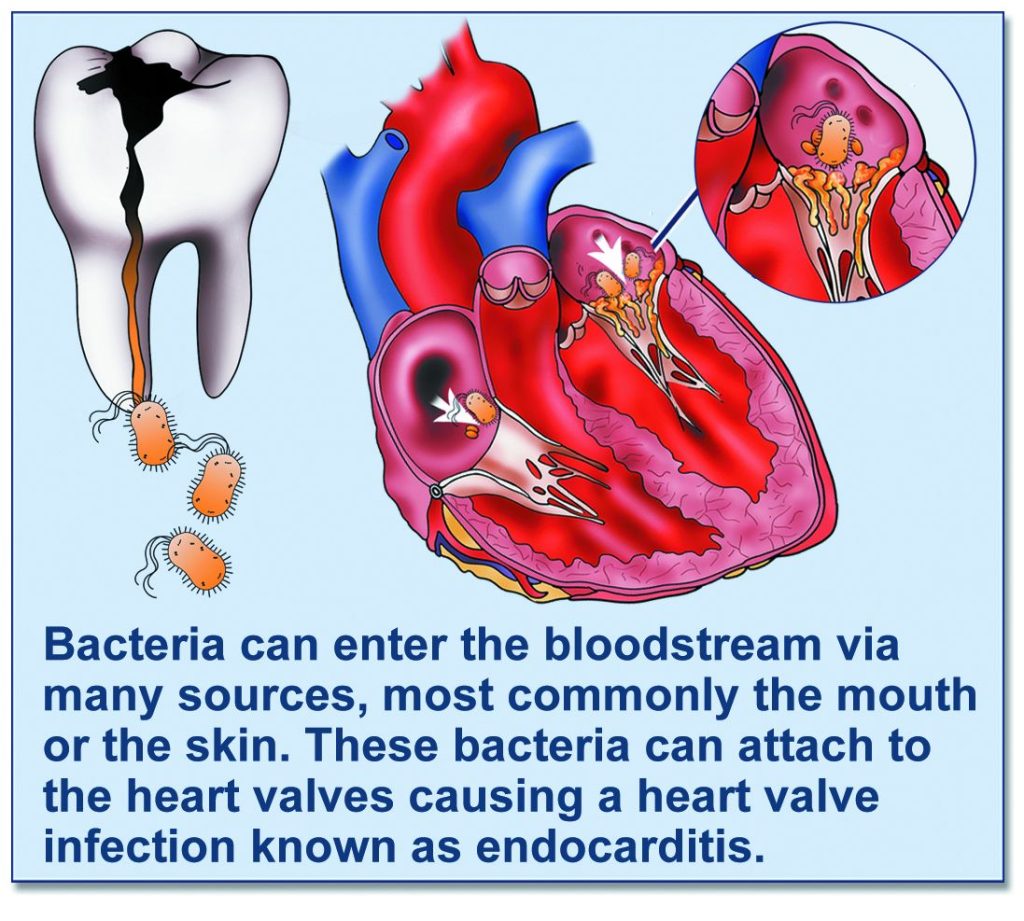

All patients will heart valve disease should visit their dentist on a regular basis to ensure good dental hygiene to reduce their risk of heart valve infection (endocarditis).

Endocarditis

Endocarditis is a rare but potentially life-threatening infection of the lining of the heart. It usually affects the heart valves. It affects around 1 person in every 10,000 per year.

It is caused by bacteria entering the bloodstream, (usually via the mouth or the skin). Most of these bacteria are killed by the immune system but occasionally they can attach to the heart valves and cause you to become unwell.

Guidelines in heart valve disease management

There are many guidelines available regarding heart valve disease management. These are designed for clinicians but may be helpful for you to read. Small details are different according to the guidelines but all offer structured advice to ensure that patients get guideline-directed therapy. Links to the main guidelines can be seen below:

2021 ESC Guidelines

2021 NICE Guidelines

2020 AHA/ACC Guidelines

BHVS Blueprint on heart valve disease